It’s a peculiar turn, isn’t it, this human obsession with mirrors, especially when they’re held up to the face of another species? From my philosophical perch, peering into the saga of Koko, Kanzi, Nim, and Washoe isn’t merely a dive into animal cognition; it’s a profound, disquieting meditation on the very limits of our own language, a Wittgensteinian echo-reverberating through the primate research labs. We sought a reflection of ourselves, a validation of our purported linguistic supremacy, and in doing so, we performed a kind of epistemic violence.

Let’s begin with the initial spark, the intoxicating idea that perhaps, just perhaps, our linguistic fortress wasn’t as impregnable as we’d believed. Washoe, the chimpanzee who learned American Sign Language (ASL), burst onto the scene, shattering Cartesian certainties. Here was a creature, seemingly, engaging in something that looked like language – signing for “more,” for “drink,” for “her,” even combining signs in nascent, intriguing ways like “water bird” for a swan. The initial excitement was palpable, a dizzying sense of discovery. Could it be that the “language-animal” (Zoon logon echon), a descriptor historically reserved for Homo sapiens, was a broader category than we’d ever imagined? This wasn’t merely about mimicry; it was about the referentiality of signs, the seemingly spontaneous generation of novel combinations.

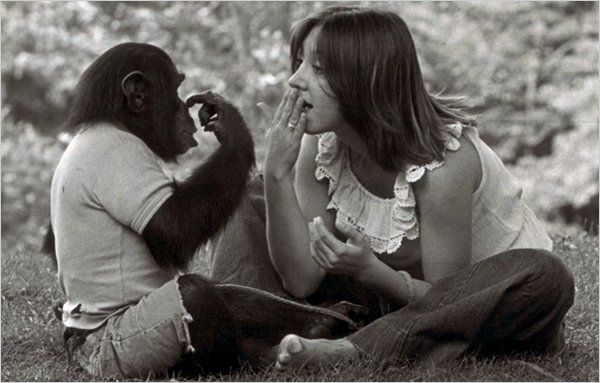

Then came Koko, the gorilla, who not only mastered a vast vocabulary of ASL but reportedly engaged in nuanced communication, expressing emotions, telling jokes, even discussing her desires. The anecdotal evidence, particularly from Francine Patterson, painted a picture of a creature not just using signs but understanding them, inhabiting a world permeated by symbolic meaning. And Kanzi, the bonobo, stands as perhaps the most compelling case, demonstrating a remarkable ability to understand spoken English, even novel sentences, and to communicate via a lexigram board. His comprehension, particularly, suggested a receptive linguistic capacity that defied easy dismissal. These were not mere conditioned responses; there seemed to be an underlying cognitive architecture capable of grasping syntactic structures, however rudimentary. The very idea that a non-human animal could, even partially, engage in what we term “language games” forced us to re-evaluate the boundaries of our conceptual schemes. It challenged the notion of a unique human cognitive endowment, suggesting a continuum rather than a chasm. The sheer audacity of these animals, their willingness to engage with us on what appeared to be our own linguistic terms, was undeniably a profound discovery, a testament to their cognitive plasticity and social intelligence.

However, the shadow of Nim Chimpsky looms large over this optimistic narrative, a stark reminder of our own biases and the profound difficulties in defining “language” itself. Nim, trained by Herbert Terrace, ultimately became a cautionary tale. Terrace’s meticulous analysis of Nim’s signing revealed a disturbing pattern: a heavy reliance on imitation, a lack of spontaneous utterance, and a primary motivation driven by reward. Nim’s “sentences” were often repetitive, lacking the grammatical complexity and conversational reciprocity that we consider hallmarks of human language. This is where Wittgenstein truly comes into play. For Wittgenstein, the meaning of a word is its use in a “form of life”, a shared practice, a communal understanding. Language isn’t just about stringing symbols together; it’s about the “language-game” being played, the context, the intention, the shared understanding of rules that are often unarticulated. Nim’s signs, when stripped of our hopeful anthropomorphism, often failed to participate in a true language-game. They were often instrumental, a means to an end, rather than an expression of an internal, conceptual framework. The very notion of “meaning” for Nim remained elusive, perpetually tethered to the observer’s interpretation rather than an undeniable, independent demonstration.

And here lies the crux of my philosophical disquiet: the cruelty of our quest. In seeking to find “our” language in Koko, Kanzi, Nim, and Washoe, we imposed a profoundly anthropocentric framework. We didn’t seek to understand their forms of communication, their inherent ways of being in the world, their distinct forms of intelligence. Instead, we sought validation for our own unique status, a reflection of our own linguistic superiority. This wasn’t a genuine interspecies dialogue; it was a unilateral imposition of our own cognitive categories. We forced them into our language-games, rather than attempting to learn theirs. We confined them, isolated them from their natural habitats, and subjected them to rigorous, often unnatural, training regimes, all in pursuit of a reflection that, in the end, often proved to be a distorted one. The true “discovery” wasn’t that animals can use “our” language, but rather the profound realization of the ineluctable specificity of human language, its deep entanglement with our particular “form of life.” We discovered that our linguistic capacities are not merely a matter of combinatorial rules but are inextricably linked to our complex social structures, our shared intentions, our unique capacity for joint attention and the intricate web of meaning we weave together. The tragedy isn’t that they failed to become human; the tragedy is that we failed to allow them to be truly ape. We sought a reflection of ourselves and in doing so, we perpetrated a fundamental ethical transgression, a violation of their being, all to satisfy a deeply ingrained, almost narcissistic, human curiosity. We should have listened to Wittgenstein’s warnings, not about the limits of their language, but about the limits of ours in understanding them.