[Text written and then not published by commission of Bulgari and Lampoon magazine]

“The individual submits to society and this act of submission is the condition of his liberation. For man, freedom consists in liberation from blind and unthinking physical forces; he obtains this by opposing to these the great and intelligent force of society, under whose protection he takes refuge.” Émile Durkheim

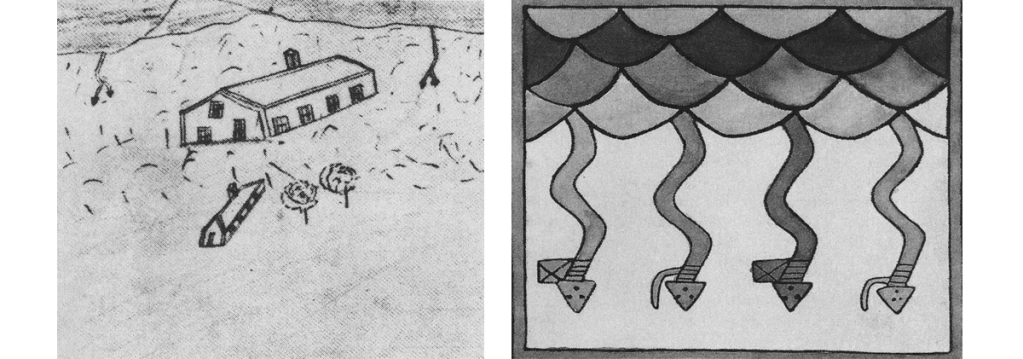

The serpent is strong; it coils without crushing and spreads the awe of reverence. Aby Warburg, in his now historic The Serpent Ritual: A Travelogue, recounted in detail the psychic power of images to both wound and heal. Warburg himself, while developing the text for what was initially conceived as a speech for non-specialists, was periodically struck by nervous crises that forced him into prolonged stays in the clinic. How can we recover lost strength? The power of images, for a man still extremely aware of ordinary scientific language, establishes a lightning-fast circuit between the mystical and the real, specifically between the serpent of the archaic Pueblo ritual and the one Moses urged to be raised in the desert. The serpent has always been the most present figure in rituals, mysticism, and the foundations of our Western and Eastern cultures. It’s no coincidence that the serpent is also the image in Bulgari’s narrative of the strong, emancipated, vital woman: there’s the Adamic reference, the idea of shedding skin, the hope of the impossibility of being trapped.

Like all pagans on Earth, the Pueblo Indians also connect with the animal world, just as we all have since the dawn of our culture—and this is what we call, with an obvious Freudian reference, “totemism.” We are driven by a reverential awe because we believe we recognize in various species the mythical ancestors of our tribes. The reason for attempting to redefine contemporary fashion as one of the last forms of sacredness in contemporary society immediately becomes clear, in the sense that sacred and profane are understood as founding polarities of humanity, at least since Émile Durkheim’s research, which alternates between the loss and reconquest of force and visions of the future. In a world where myth seems to have disappeared, and with it therefore rites and rituals, the world of fashion, with its changes of clothes, masks, and indeed serpents, provides us with the condition for possibly re-sacralizing the world. Without rhetoric, what’s at stake is a new vision of reality that rests in its ancient animal face.

Warburg is an interesting tool for understanding something about Bulgari’s serpent-woman. The serpent is revered among the Pueblo for its intelligence but also, and above all, because it is a stylized figure of lightning. Bulgari’s woman, in this sense, is precisely this: the boundary between heaven and earth, or between the world of animal strength and human weakness. The serpent, through the ritual by which we try to understand it, can facilitate rain, and then the rain fertilizes the earth. Creation and destruction, embraced forever. It’s no coincidence that Warburg connects the Pueblo practice with the Maenads who dance with serpents coiled around their arms (a proto-community of a feminism yet to be explored), but also, of course, with Laocoön: the prophet wrapped and buried by sea serpents. The serpent is a figure multiplied almost serially in traditions and reaches our seemingly ritual-free society of customs: it is what kills us and therefore also what saves us. Asclepius, the ancient god of health, has the serpent coiled around his staff as his symbol (a symbol seen today in every pharmacy around the world). His features are those that characterize the savior of the world in classical sculpture, while in the Bible, on the contrary, the serpent causes the fall of man, but the “bronze serpent” raised by Moses, at God’s instruction, saves lives, and “whoever looked at it, lived.”

It is precisely on this dual nature of salvation and misery, cage and emancipation, freedom and constraint, that Bulgari’s serpents embrace the contemporary woman: stereotyped, treated as an object, yet today a shaman of a coming world where power dynamics are completely reversed, aiming to create communities and futures in a new and combative way.

Warburg-Bulgari, then, following the false line of an anthropology and archaeology of fashion, helps us to explain that among the formidable powers of those who believe in the serpent-woman will be that of being baptized and saved, acquiring the ability to turn the serpent into virtue, scandal into norm, poison into pride – “These are the signs that will accompany those who believe: in my name they will cast out demons, they will speak new tongues, they will pick up snakes with their hands, and if they drink any deadly poison, it will not harm them; they will lay hands on the sick, and they will recover.” Speaking new tongues is akin to the power of handling serpents, and these are the female figures of Bulgari, well-installed in the broader software of the current need for the final emancipation of gender: heroines of a new world in which every form of patriarchy is completely overthrown, subverted, de-ritualized. They have the ability to drink the poison with which society has trapped the feminine, and their tongues, like those of vipers, are forked: they whisper arcane secrets, open up to the mystical world of tarot cards and the possibility of influencing futures by re-reading the pasts, drawing astral themes of independence and assisted conception. Bulgari’s necklaces and bracelets are then like the serpent cast by Moses: he dies, but if you look at it, you will live and have the task of the new world on your shoulders. Will you finally be able to manage it?

The serpent is therefore the cyclical symbol of time, the eternal return on Friedrich Nietzsche’s Lake Silvaplana – the Ouroboros – following the vertebral latitude of the human – what we increasingly call today the Kundalini. The yoga of the serpent, spiritual liberation through the taking of that Bastille unjustly occupied for too long, which is the body of women.

The serpent is therefore a universal symbol, traversing every culture, and is understood as an answer to the central question of our lives: from where do the fury of the elements, death, suffering, pain, injustices come? How can we create art, fashion, design, with the terrible awareness of death and the serpent’s bite?

Fashion, more than any other creative discipline, is precisely this: a possibility of bridging the abyss of mortality through the immortality of the mask.

Our age, that of advanced capitalism, which paradoxically is the same one that creates the industrial and cultural possibilities of fashion, does not need the serpent to explain and understand lightning. Everything is secular, devoid of history, smelling of flatness. The reason is obvious… Lightning no longer terrifies the inhabitant of the big city, nor do the inhabitants of Milan or New York, Paris or Berlin, Moscow or Bangkok await the beneficial thunderstorm as the only source of water (or perhaps today, with climate change, something is changing?). Humanity today has technology, and the lightning-serpent is harmless: it strikes the ground directly from the lightning rod, it doesn’t even scare us if it hits one of our many Faraday cages like airplanes. The explanation provided by the natural sciences sweeps away mythological randomness, and perhaps even woman loses her mystery in the age of biological sciences lent to gender studies. Warburg tells us something that I believe is very useful for understanding Bulgari’s strength: we know that the serpent is an animal destined to succumb if man wishes it: there is no pure form of modern technology that cannot, suddenly and decisively, erase every magic. The apparent reason? The replacement of mythological randomness with technological randomness eliminates the dismay felt by primitive man towards mystery (which still remains and shifts? Who really knows what a black hole is? Another mystery).

But where has this pure and genuine mystery really gone? Fashion works on a central gamble for contemporary “developed” societies: the human freed from mythological vision cannot immediately provide adequate answers to the enigmas of existence. Technology frees us from dismay, certainly… but it also frees us from the basic condition of aesthetic experience, namely wonder. Every form of the present space is clean, jacket and tie for work, but nonetheless it does not appear purified, and the reason lies in the rebellion of Bulgari’s serpent-woman: the pure is accessed through violence, even if it is often a substituted violence. Of course, we do not slit the calf’s throat in the square or burn women as if they were witches, but we eat a slice of meat or consume girls in Dutch shop windows, both so pleasant and rosy – and even if we decided not to eat meat or to free enslaved women, this does not lead us back to the sacred yoke in which the ox or the feminine become fundamental elements for understanding life. To be one again, at one with masculine and feminine, between humanity and animals, a single revolutionary ego that tastes of Spinoza’s nature or Averroes’ mind, we must re-inhabit the serpent ritual.

Contemporary fashion revives humanity’s old struggle against nature. The ancient struggle against nature, seemingly brought to a successful conclusion by capitalism, is now regaining prominence in the age of ecology as the dominant narrative: now that everything is collapsing, who really won their challenge? Apollo or his earthly children? Technically exploited, nature was subdued: and woman, in her history of discrimination, has always been seen as non-cultural nature. Nature as an immense enemy, as a female animal: and then industries, factories, work clothes, the feverish anxiety of commodity exchange, the functional removal of the city-country distance. “Stripped of spirituality,” as Hugo von Hofmannsthal defined early 20th-century Europe where fashion began to take hold, and where every commodity is a useless creation for the spirit: everything is subjected to money, the occult influence of the new serpent we call “the market.” The ambiguity of Bulgari’s actions is the threshold of revolution: let the serpent return, as in the Pueblo ritual, and let us bow before the real winner of this battle between technologies and the woods. Nature has won, long live nature.

Is everything we have lost in this struggle of technology clear then? Perhaps we are facing a new direction that I seem to be able to read as a new sacrifice: the dissipation of the sacred, the end of mystery in human societies. Warburg, moreover, gave the lecture that pivots these pages among the sick and doctors, reminding us that always, where evil, illness, the alien, the monster seethe, there lies the beginning of salvation. What a decisive gamble for contemporary fashion… the monster as an image of a future in which humanity will re-embrace the foundational myth of all cultures.

The Pueblo people used the serpent through dances, essentially, with the excuse of causing rain. There were therefore three forms of dance:

(1) Man imitating the animal, or the antelope dance; (2) The dance using masks and small statues or dolls (“kachina”) performed around a tree covered with feathers, which are detached from the tree and taken to a spring – indicating the relationship of union between air (feathers = bird) and water (sign of rain). The serpent, in this case, is thus used as a mediator between man and the Rain God (the bird and the serpent are seen as the same animal; indeed, there is talk of a feathered serpent… the bird also seen as a classic messenger). (3) The dance performed with live serpents, rattlesnakes. The Hopi (to be reductive, the shaman) is convinced that the serpent will not harm him, and a certain harmony is established between man and animal so that the serpents are placed around the man as in an embrace. The serpent is prepared the day before and is washed, purified, brought to a square, and after the ritual is immediately released so that it can “carry the message.”

I would add a fourth dance here, that of Bulgari – a dance of powerful, creative, revolutionary fashion. The serpent dance has always had a double value in its symbolism: it sheds its skin and therefore represents a rebirth (life), but due to its phobic charge, it certainly represents a negative aspect (death). We dance between life and death, we dance at the end of the world, we dance because we move and die every day and are reborn as priestesses of a new world yet to be invented.

A good anagram of “serpente” (serpent) is “presente” (present), the gift of the here and now that Bulgari’s women embrace with their renewed awareness. The serpent thus becomes the metaphor and symbol of a contemporary world where the future is no longer an articulation of the present, and where this continuous voracity feeds the sensation of a fragile and ephemeral reality that feels its primordial matrix in the transient. Bulgari’s serpents are heterogeneous material expressions of a ravenous contemporaneity: a serpent attacks the neck, tangles of materials that look at us with glassy eyes, extrapolated architectures that play a role of artificial monumentality, interior female landscapes with uncertain contours, imaginary beauties seen from above, an informal but elegant language that holds a sense of precariousness, of hoped-for conquests and distressing awareness. A cultural journey in search of a natural gaze, of an uncontaminated contact with the image in the constant loss of referential points where it is possible to let oneself be captured by the saving power of a work of art that is current fashion.

Bulgari’s woman is an invitation to the serpent charmers’ feast, perhaps the possibility of a possible collaboration. In Abruzzo, on the first of May in Cocullo, in the Aquila area, San Domenico is celebrated, and, as with most Italian customs where pagan ritual intertwines with Christian devotion, so it happens on this occasion: the devotion to San Domenico, protector from snake bites, intertwines with the archaic rite of the “serpari,” snake handlers, in the evocative and unique Rite of the Serpari. For the feast, the statue of the saint is carried in procession, adorned with tangled, harmless little snakes particularly well-known in the mountains around the village, including Whip Snakes, Four-lined Snakes, Western Green Lizards, and Grass Snakes. The so-called serpari collect these snakes in the mountains around the village during the cold season, during their hibernation. Before the procession, these men show the snakes to visitors, allowing them to touch and handle them, while folk songs are sung through the streets of the village. The ritual, therefore, rather than disappearing, seems hidden in pockets of resistance to a capitalist society: the village, the procession, the meeting place as resistance to forced labor. After the holy mass, in the late morning, the statue of the saint is covered with snakes and the procession thus begins; in fact, without any methodological forcing, it seems like watching a fashion show. The procession stretches along the narrow streets of Cocullo, almost like runways of possibility, transmitting to the public, who, as in a Bulgari fashion show, hopefully experience the evocative and emotional images of an unprecedented encounter between the wild mystic and the technological human from the front rows. A different day, which breaks the rhythm and style of contemporary societies, and which reconciles souls with nature, and calms hearts by anchoring past times with eternal suggestions – suggestions that offer a small, unspoiled mountain village the typical idea of fashion theater: the absolute is here. A single hook, from anthropology to fashion to the archaeologies of the sacred, leads to sharing in devotion mixed with folklore. The dress is the glass ceiling of this break from the ordered and ordinary world in which we interpret our narrow roles, completely different from animality. The encounter with the serpari, the possibility of stroking a snake and overcoming fears like a enveloping necklace caressing a neck without drowning us, and then crowding behind the statue of the saint asking for help for health – as has always been done with women, the healers of every historical era.

But there is also simply remaining on the sidelines, a spectator in front of such a particular event, a rediscovery of wonder that inevitably arouses a deep thrill worth experiencing.