Once upon a time, in a tiny, tiny world, there was perhaps a family of hens. No one knows why they were there; they simply found themselves in it. Much like us in our own world, for that matter, we just found ourselves there too. Their world, however, is anomalous, full of boundaries. No one is certain where it begins or ends, but it seems particularly narrow and crowded. It’s dark. Every now and then, there’s a bit of light, intermittent. And it’s a light that goes “this way and that,” “this way and that.” Perhaps it’s a fairy tale world, but a bit topsy-turvy. Maybe there are three hens, but even when… what does it matter to count them?

So this is how the story begins: “Once upon a time, in a world far and near, a small group of hens…”

Hen X: “There’s no space, move or I’ll peck you!” Hen Y: “This space is mine too, you move!” Hen Z: “Can you both be quiet? I’m trying to expand the world! I’m trying to find its light.”

Hen X: “Cluck-cluck… are we doing this right?” Hen Y: “-.-‘”

It’s a cramped cage, but it’s all they have. Just as our world is all we have. The boundaries are often the limits of their bodies; it’s hard to understand their relationship. A mother, two daughters? Three sisters? But then again, they’re just three hens, or perhaps four, or maybe they’re even just one: “the hen,” the concept we’ll eat that makes all possible hens equal. What are male hens called? Roosters? Cock-a-doodle-doo.

Hen Y: “Peck, re-peck, peck again. The world really seems to be this, and it’s not getting any bigger.” Hen Z: “I’ll peck you, I’ll eliminate you: that way the world gets bigger because there are fewer of us.” Hen X: “Silence! I hear something outside the world, an unusual but constant chatter.” Hen Y: “Sometimes I just want to be my eyes. Eyes are the landscape.” Hen Z: “…well, we even have a philosopher among us… how lucky.” Hen Y: “Go kill yourself.”

Outside the cramped world, there’s a larger world: no one sees what’s in front of them, making it difficult to understand that the boundaries we perceive are nothing more than the limits of our possible world. But the world is bigger.

Hen X: “Incessantly, I peck at every side.”

What’s the sound of a hen? Does anyone REALLY know the sound of a hen?

[Clucking (or croaking) is the characteristic sound made by a hen to call her chicks or when she wants to express a need.]

Hen Z: “I’ll peck you, I’ll eliminate you: that way the world opens up because there are fewer of us.” Hen Y: “Crocck… Crockkkk…”

But there are no more chicks here. They were ground up in an uncertain space, outside the cage. They were males, a useless sex: unproductive. The manifesto of the elimination of the male, or of hens.

Hen X: “I’m going crazy, I want to explode.”

Hen Y: “Explode, and you’ll make space for us.” Hen Z: “There’s a smell, you need to stop doing it on me.” Hen Y: “You’re the one coming where I did it. You’re in the blue.” Hen K: “I’m here too, damn it.” Hen Y: “And who are you? Do you have a name?” Hen K: “But why, excuse me, what’s your name?” Hen Y: “12579”

But here, nothing belongs to anyone; everything belongs to no one. Numbers, rather than lives. The animal world is made of cute, stylized images, like unsuitable puppets for reality: how cute the hen is! How I wish I had one all to myself! But instead, the hen is the omelet. An omelet made of silence, salt, a little pepper.

[An egg is a food item that can be consumed directly or as an ingredient in numerous dishes worldwide. The egg is a female germ cell.]

Hen Y: “Where have my little ones gone?”

Hen Z: “They were mine!” Hen X: “Quiet, quiet, quiet. They were mine, where are they?” Hen Z: “It was that light, that sudden hole in the box.” Hen X: “What box? I see the sun, I smell the fragrance. The fragrances!” Hen Z: “Is it the scent of the little ones?”

The life of the act, that of potency. How much mysticism about the egg! Easter, and then the colored egg, Columbus’s egg. And meanwhile, life reproduces, it becomes a spectacle: could we ever live in a world without English breakfast? I would prefer not to.

Hen X: “Wild herbs or salads, small insects, earthworms, snails, and grains. This is what I would like to eat.” Hen Z: “I, on the other hand, would like to eat you.” Hen Y: “Will you stop biting me?” Hen Z: “Do you know the last time I ate?” Hen Z: “Do you know I don’t care?”

Hen Y: “Do you know there’s a strange smell?”

The limits of our language, human, all too human, are the limits of what we can see or perceive. What’s truly inside the box? This box, which is ultimately a box-world. What must be abandoned to truly discover it? Isn’t yellow also a kind of pink?

[Laying hens need little to be happy: a fenced area where they can roam freely, shelter from the rain, feeders, drinkers, and nests will suffice.]

Hen Z: “I can’t feel my legs anymore. Everything hurts. I’ve been in this position for months.” Hen Y: “Look, we’ve been here for two hours.” Hen X: “But it must have been years that we’ve been inside this thing with no outside.”

Hen K: “Anyway, I’m not doing so badly. You complain for no reason.” Hen Y: “Cluck.”

The time of life is different from the time of death. Only he who lives immersed in his world without ever seeing its boundaries lives eternally. Reality is a form of superstition.

Hen Z: “I can’t do it anymore. I want to stop.” Hen Y: “Stop what? Quiet, don’t rave.” Hen Z: “Stupid hen.” Hen X: “But it must have been years that we’ve been inside this thing with no outside.”

Hen Y: “You’re going crazy.” Hen Z: “At least we weren’t born that way.” Hen Y: “But then outside or inside what????”

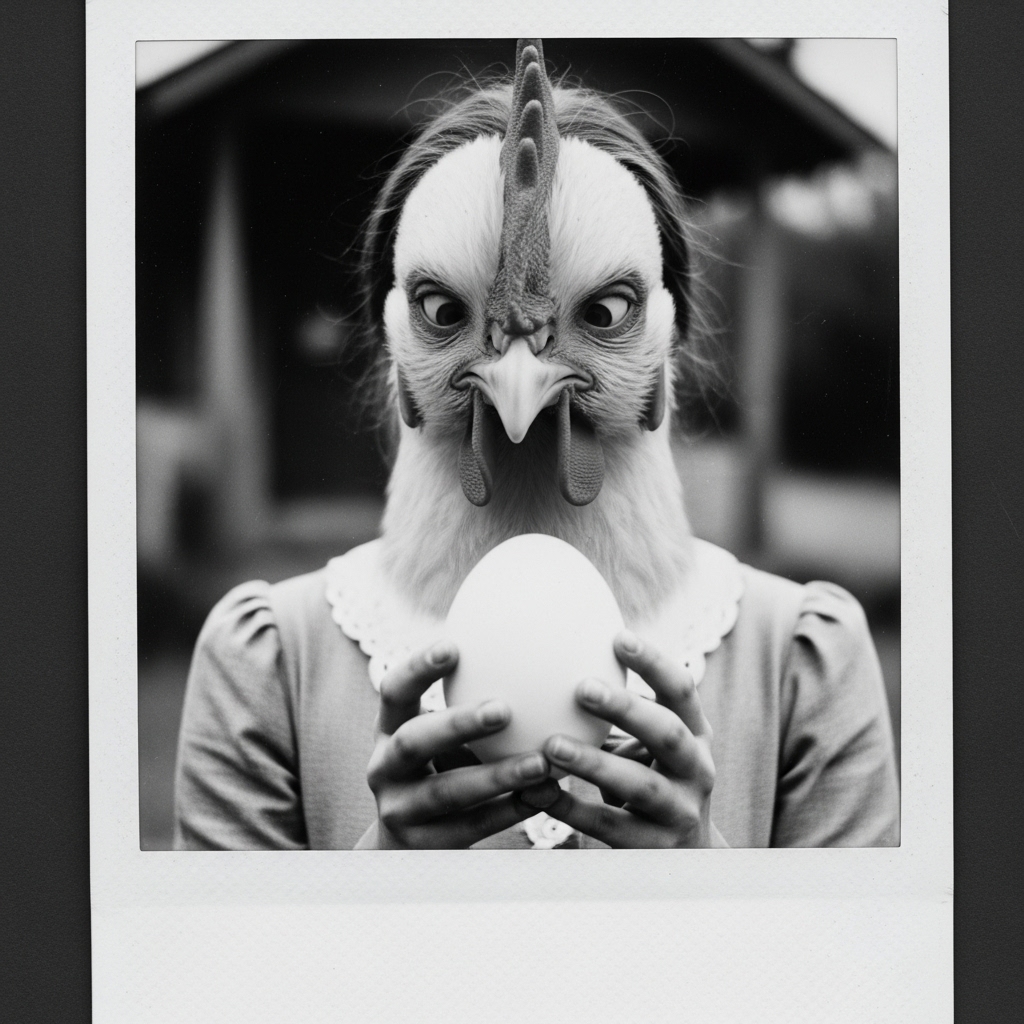

Smart as a hen. Where does this unhealthy idea that they are stupid come from? And what are hens really like? Who are they? What do they do? How do they look or look at us? The hen, its diversity, forces us to start asking ourselves again: what is human? And its opposite… the inhuman?

[Hens have a true language made up of vocalizations and mimetic behaviors that serve to communicate different types of information. This demonstrates their self-awareness and awareness of others: in short, they are very intelligent beings. Technically, they are much more intelligent than a six-year-old child… Lesley Rogers, one of the world’s leading researchers in neurology and animal behavior, discovered cerebral lateralization in hens when it was believed that only the human brain was divided into two hemispheres with different specificities.]

Hen Z: “There’s blood everywhere here.” Hen X: “Was that blood????”

Hen Y: “What else could it be?” Hen Z: “Did you drink it?” Hen X: “Ahhhhh… cluck cluck cluck.” Hen X: “There’s not even talk of drinking here. What is this stuff?”

Ultimately, the world, whatever its symbolic form, is the ability to perceive it. Each world is closed to every other possible world. Do we then see these other universes that surround us? Do we observe that we might also be observed by those who live confined in worlds different from ours? What is the point of studying art if all it does for you is enable you to eat, in a relatively plausible way, someone who has lived in darkness? On some abstruse questions of ethics, if art doesn’t improve your way of thinking about the important issues of everyday life, then it’s useless? If it doesn’t make you more aware of any hen regarding the use of the dangerous images that cross our paths, then everything is useless.

Hen Z: “If we’re lucky today, finally, we’ll die.” Hen Y: “But what is death?” Hen X: “Death is a box.” Hen Y: “No, death is liberation.” Hen K: “Can I have some seeds to eat? Thanks.”

[This text was written for an exhibition and a project with Nico Vascellari. It was not used later].