The First Image of the Motorcycle.

La metafísica de las cualidadesdonde literatura y filosofía se encuentran

There it was, that photograph, my father on a white BMW, dressed like a sailor. It hung in the hallway, that strange one near the laundry room; it seemed to me he was utterly free. Where was he going, and why? I didn’t yet understand that one doesn’t ride a motorcycle to go towards things, but through them. For a motorcyclist, arrival is always a problem, an obstacle to be circumvented: the issue isn’t reaching a destination, but hoping to travel forever. To never be fathers, to remain sons eternally.

A philosophy of the motorcycle, then, is a theory of freedom as an end in itself, a continuous maintenance of the conditions for the possibility of an absence of responsibility. It’s an embrace of the transient, a dance with the unpredictable, where the journey itself is the only true constant, and the horizon forever beckons without demanding a final embrace. The engine’s hum becomes a mantra, the wind a silent confidant, and every mile marker a testament to a life lived unbound by conventional anchors.

It Wasn’t a Motorcycle.

The first time, at thirteen, it was on a small, sky-blue Honda moped. It certainly wasn’t a motorcycle, but the intuition it sparked was invaluable: why would I ever dismount from this? What could be more precious than transforming instability into stability through an equation of speed? How could I ever separate myself from something that floats in the wind? It wasn’t a motorcycle, but it was a training in anticipation of one: a throttle pulled hard towards oneself with the palm of the right hand, a poorly fastened white bowl-shaped helmet on my head, and before me the infinite possibilities of wandering without any need for a port of call… “to the vagabond life, to the contemplation of pain, of death, of the uncertainty of every activity, compelled to fix one’s eyes in the abyss.” This nascent experience was a revelation, a whispered promise of a larger freedom. It was the embryonic stage of a deep-seated craving for open roads, for the solitude of the journey, and for the profound connection between human and machine, a bond forged in the crucible of velocity and balance.

The Fall.

Two wheels balanced in the wind are metaphysically connected to their final cause: they can always fall. That first fall, in front of school at fifteen… everyone’s eyes on me, and then that echo of laughter. But every motorcyclist knows that the point takes the shape of a knot; only those who constantly risk falling, by metaphysical law, learn to get back up quickly. And to repair, perhaps I would say above all, and therefore to care for a bodywork with the same elegance as a wound, but never completely hiding the damage. The experience of failure, in a philosophy of the motorcycle, is after all a medal. I fell, and in my curriculum, it holds the same space as a courageous turn. It’s a badge of honor, a testament to resilience, a reminder that the true spirit of riding isn’t found in flawless execution, but in the unwavering commitment to keep going, to learn from every scrape and dent, and to carry the scars as stories of journeys truly lived.

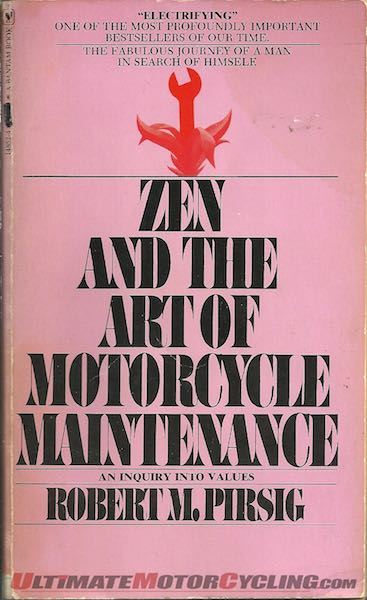

So, here you are. You hold a book that, on the surface, appears to be a simple account of a motorcycle journey. But, believe me, Robert M. Pirsig did not write a travel guide. He wrote a manifesto, a philosophical treatise disguised as a road trip, which, if read with the right eyes — those uncontaminated by the logics of profit and authority — reveals a disruptive potential. I am speaking, of course, of a profound resonance with what I call the anarchy of living, a degrowth of the soul, and a silent rebellion rooted in the ethics of care.

The motorcycle, for Pirsig, is not just a means. Nor is it for me. It is an extension of the body, an extension of the will, and, crucially, a symbol of autonomy. One doesn’t ride a motorcycle to be transported, but to be in the journey. To “be” in a deep, radical sense. The very act of riding, of feeling the wind, of calibrating the balance between speed and stability, is a practice of self-governance. There is no hierarchy between the rider and the machine, only a symbiosis born of mutual understanding and respect. This, my friends, is the first, fundamental step towards anarchy: the abolition of the master-slave relationship, even with the technology that surrounds us.

But the pulsating heart of this book, what makes it an almost prophetic text for our times, is maintenance. The “doing.” Pirsig is not talking about mechanics for its own sake, but about a metaphysics of the bolt. It is not about simply fixing something that is broken; it is about engaging, intimately and critically, with the object of our interaction. This hands-on engagement, this meticulous attention to detail, is an act of deliberate resistance against a world that constantly pushes us towards delegation, towards externalizing our capabilities. We are taught to consume, to replace, never to repair, never to truly understand the workings of what we possess. This systemic disempowerment, this alienation from our own agency, is precisely what perpetuates the very hierarchies we seek to dismantle.

Consider the Quality. Pirsig’s elusive, yet central, concept. It is not something to be found in a manual, or dictated by an expert. It is an intuitive understanding, a holistic apprehension that transcends the sterile division between the “classical” (rational, analytical) and the “romantic” (intuitive, aesthetic). For me, this is an inherently anarchist pursuit. It is the individual’s sovereign quest for meaning, refusing to be confined by pre-established categories or authorized narratives. It is the rejection of an imposed epistemology, the recognition that true knowledge, true value, emerges from an engaged, personal experience, not from the pronouncements of an authority figure or institution. It is a rebellion against the epistemic violence that categorizes and diminishes, instead embracing the fluidity and interconnectedness of all things.

And then there’s Zen. Often misinterpreted as mere calm or passive contemplation, Pirsig shows us a different face: the Zen of meticulous action, of being fully present in the task at hand. This is not about emptying the mind, but about filling it completely with the intricate dance of parts, the subtle vibrations of the engine, the precise torque of a nut. This deep immersion, this mindful engagement with the material world, is a radical counter-narrative to our contemporary obsession with speed, efficiency, and instant gratification. In a world spiraling towards ecological collapse due to our relentless consumption and detachment, the Zen of maintenance offers a profound lesson in degrowth. It teaches us patience, care, and a renewed appreciation for longevity over novelty. It is an ethical stance, an anti-speciesist empathy extended not just to living beings, but to the very matter that constitutes our world. To care for a machine, to understand its needs and limits, is a microcosm of caring for the planet itself, for the intricate web of life.

The journey itself, the physical act of riding across America with his son Chris, is a metaphor for the human condition in its purest, most unadulterated form. It’s a journey without a pre-ordained destination, a constant becoming, a defiance of fixed points. This is the very essence of anarchic freedom: the ability to chart one’s own course, to embrace contingency, to derive meaning from the process itself rather than from an externally imposed outcome. The tensions with Chris, the unraveling of Phaedrus (Pirsig’s former, more radical self), are not just personal dramas; they are allegories for the internal struggles involved in shedding societal conditioning, in challenging one’s own assumptions, in dismantling the mental prisons we construct for ourselves. Phaedrus’s pursuit of the Quality, his ultimate breakdown, is the price often paid for such intellectual and existential rebellion – the painful but necessary dismantling of the old self to allow for the emergence of something more authentic, more free.

“Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance” is, therefore, far more than a book about motorcycles. It is a profound meditation on how we live, how we relate to the world, and how we might reclaim our autonomy in an increasingly controlled and commodified existence. It’s an invitation to a personal revolution, a quiet, decentralized insurgency where every tightened bolt and every moment of focused attention becomes an act of liberation. It teaches us that the path to a truly anarchic existence is paved not with grand pronouncements, but with the meticulous, mindful, and deeply ethical engagement with the reality that surrounds us. And, in that sense, Pirsig’s work remains a vital and urgent text for anyone seeking to live a life of true freedom and conscious responsibility.