1. Mediterranean Premise.

Yet, once, this sea was nothing more than a swift bridge to cross. There was a language, Sabir, that everyone spoke: the Mediterranean, perhaps, was in its own way a separate State. The ship departs from Palermo, bound for Tunis, while Carlo Alberto Giardina and I are laden with musical instruments and recorders. Our commission, more or less clear, is to research the Gombri and traditional Tunisian sounds. Together with Carlo and Roberta, we animate a research collective, Rethinking Lampedusa with the Made Program from Syracuse, which for many years has been trying to understand how to reconnect the broken Mediterranean. I’m returning to Tunisia for a second time, after conducting research with CIS Tunis (which deals with “return” migration), to interview Salah El Ouregli. A dear artist friend, Aymen Mbarki, with whom I’ve worked for a long time, tells me, “I know him. He’s one of the few who still plays it.”

What is the Mediterranean? A dirty, trivial, temporary working definition: the sea and its coasts understood as a metaphor for the ensemble of cultures, histories, traditions, and lifestyles that have developed in the Mediterranean basin, influencing each other over millennia. The Mediterranean is an extra-territory: it spans multiple continents, de-obstructing many of the geopolitical norms that govern its forms. Leonardo Sciascia called the Mediterranean mari-amaru (bitter sea), an expression that encapsulates much of the vision that, in this obstacle course, has led me to this latest journey to understand something. Bitterness, a crossroads of invasions, suffering, and isolation. At stake, as Federico Campagna awkwardly and not very precisely puts it in his Otherworlds Mediterranean Lessons On Escaping History (2025), is a radical but always minority epistemology: an idea of right and wrong, of time and speed, of process and human nature, a way of knowing intrinsically different from the very way that has led me here, at almost forty, to write my books in a certain way. It’s not easy.

“Physics is on the wrong path. We are all on the wrong path”… this is a historical, perhaps over-interpreted, phrase by Ettore Majorana. It’s the morning of August 3, 2023, and thanks to a friend and heir, I have the opportunity to speak with his nephew at the family villa in Catania: “Ettore wasn’t normal, but let’s not forget he was above all a Catanese… an irregular, a restless soul, a disappeared person by definition.” In reality, at least this is what I’ve become convinced of after consulting archives, reading books, and speaking with family members, Majorana’s disappearance is above all an epistemological issue: choosing withdrawal, the elsewhere, as one of the possibilities at play (subverting, in fact, the main social game we are all engaged in). “A Catanese… an irregular,” in the sense of a man from the South: a physicist of the Mediterranean. And I, who am a philosopher of the Mediterranean, what do I have to say about this story? As Carlo and I are on the ship, I think, Majorana perhaps disappeared in a place like this. Since I had the idea to start writing a book about the Mediterranean, the reason why I also won the chance to take this other trip, many things have happened that, to put it mildly, have slowed me down. Ideas circulate, and some arrived long before me: I told myself I had (at least) two options. Throw the book away and dedicate myself to something else, or go ahead and do it my way: meanwhile, write travel reports that were not just about the Mediterranean, but that were the Mediterranean itself… circular, fluid, full of wasted time and yawns. Of personal considerations, anecdotes, of a philosophy that doesn’t just live its time but, precisely, “kills it.” Wasting time, which implies at least two things (a concept of time well spent, and a convention of time that never goes back), is not always a bad thing: in the meantime, there have been atrocious wars, new European balances, vast stretches of failed epistemologies and philosophies under the weight of daily material reality. I will call this contemporary condition, in the course of this work which I inaugurate here, the “post-Mediterranean condition”, symbolized by an idea of a future in which Europe and the Mediterranean are intrinsically linked, and European thought, now minority compared to emergent thoughts from other latitudes of the world, emerges from this fertile union. This is the era of “Euromediterra” that we will explore, a historical moment where old post-twentieth-century thought systems have failed even in their critical repercussions that had developed into a critique of those systems but nevertheless used the same logics.

2. Tunis, Southern Italy

Arriving in Tunis, once again, it feels like a piece of Southern Italy. Mediterranean music seems to resemble itself everywhere; there’s no Frontex border to divide its geography, its geo-music, and this allows Carlo and me to make our first recordings for our meditations, which feel the same as those we could have made in Palermo. The political climate in Tunisia, at this moment, is dynamic… Kaïs Saïed (Arabic: قيس سعيد, Qaīs Sa’īd; Tunis, August 29, 1958) is a Tunisian politician and jurist, a professor of constitutional law, president of the Tunisian Republic since October 2019 and re-elected in October 2024. He’s very close to Meloni, he has re-stabilized the situation post-Arab Spring, he “helps” in blocking migrants, which our government likes so much. Yet, once, this sea, as I said, was a crossroads for fishermen and adventurers: the only frontier was hope. We settle in the Medina, now gentrified in pieces: Ballarò, in Palermo, seems more Arab than here. To myself, I thought that for me, the Mediterranean coincides with Caravaggio’s places of escape: Sicily, Malta, now crucial points of the migration crisis. It’s no coincidence: places of arrival and escape where it’s easy to hide. By dedication, they are therefore more real, authentic: here, foreigners feel less foreign.

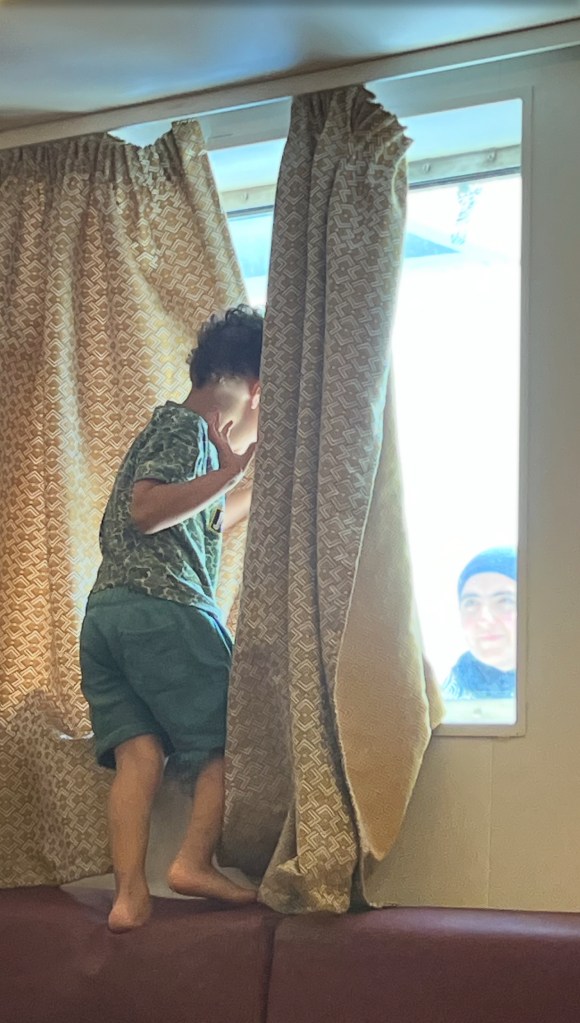

Tunis, already on the ship from Palermo. Hundreds of bodies sprawled on the ground to sleep. Me, with them. The Medina, instinctively, recalls any neighborhood in one of our large Southern cities: no point in beating around the bush, Sicily instinctively prepares you for “third worlds.”

3. Western Civilization, Bad Bunny

For our conference and performance, we’re assigned a kind of rooftop at a famous downtown hotel, on the twentieth floor (Habibi downtown): from above, this immense Trapani we call Tunis is all white roofs with red flags. An open-air theater of many contradictions. On the shores of the Gulf of Tunis, Carthage was born as a Phoenician trading post in the 9th century BC, literally the cradle of all Western civilization: Wikipedia reminds me that at its height, it was the capital of a small empire that included the southeastern territories of the Iberian Peninsula, Corsica and southwestern Sardinia, western Sicily, and the coasts of Libya. I, Carthaginian. Today, July 8, 2025, the news of the rejection of Matteo Piantedosi (and the European delegation) from Benghazi is everywhere in Tunisia: the full autonomy of the Maghreb, the need to deeply rethink these hallucinating collaborations with Europe for the “management of migratory flows”… the fundamental rethinking of the role of what Toni Negri called the “New Barbarians” (in Empire) who break every established political geography. I see newspapers with the minister’s face hanging in the local markets… the world, for better or worse, is already changing. Tunisia officially maintains neutrality in Libya’s internal conflicts, but actively supports reconciliation efforts between the various Libyan factions in cooperation with Egypt and Algeria. This part of the world, so important, holds the boundaries between our universe and something that, since the death of Gaddafi and with the “Arab Springs,” appears indecipherable to us. Meanwhile, hordes of teenagers chase me to sell me Adidas designed by Bad Bunny… they are almost identical, and the art of counterfeiting fashion (and not only) is something through which we could understand a great deal about these peoples, for whom reality and imitation of reality blur into the sole desire to “resemble” the non-existent myth of the European bourgeois—a myth we clumsily continue to sell. Piantedosi, put back on that plane: autonomy, counterfeiting.

4. At the Lampedusa Café

Since March 2025, a strong emphasis has been placed on strengthening North African border security. Not so much the borders that separate “us” from “them,” but their “them” from “them”… Black Africa. Representatives of Libyan and Tunisian military and security institutions, facilitated by UNSMIL, have agreed to establish a specialized research center for border security studies. Officially, it sounds like this: “the focus is on improving coordination, information sharing, and addressing threats such as terrorism and irregular migration.” In practice, the racism we have towards hundreds of Tunisians on boats bound for Lampedusa is nothing compared to what thousands of Tunisians have towards those trying to cross the hell of the Sahara northward. Yet, until August 2023, Tunisia and Libya had reached an agreement to cooperate in receiving sub-Saharan migrants stranded at their shared border, highlighting the ongoing humanitarian and security challenges in the border region. The dehumanization of this world, while we still talk about the urgency of “separate waste collection” (here, collecting debris from the ground is less simple than emptying the sea with a straw), continues at a violent pace. Meanwhile, the “Lampedusa chimera” continues to generate the most unthinkable dreams and products, and hundreds of Tunisians, with virtually irrelevant passports, continue their death crossings in the central Mediterranean. I enter the “Lampedusa café,” and with my clumsy French, I speak to the owner: “I work there every year, you know?”… “My son died trying to reach it, so to remember him, I named it this.”

5. One Morning I Woke Up

In the morning, at breakfast, on the roof of the Tunisian building where I’m staying, a strange Egyptian version of “Bella Ciao” plays like a mantra: the video, somewhere between La Casa de Papel and a porn film, shows half-naked girls twerking. I ask my host, “Do you know what song that is?” And she says, “A very cool Arabic dance song.” History, today, is this: a counterfeit in itself, like on social networks where true and false are just two moments of phenomena now leveled and crumpled into nothingness. They give me some dates, while I await some local intellectual voices for the interviews I need to do, and meanwhile, from the window, I begin to hear the muezzin (the person in the mosque tasked with calling the faithful to Islamic prayer, ṣalāt, five times a day) summoning the neighborhood. This absurd dance version of “Bella Ciao” mixes with the adhan, the traditional call to prayer, and for a moment, it feels like I’m experiencing all of contemporaneity in a single gesture. How empty, I think to myself, are the discourses of so many colleagues about the present. How little of the world has entered them, how little of that “knowledge that others don’t call knowledge,” as Paul B. Preciado would say, have we allowed ourselves to be penetrated by. All of us.

Everywhere, Palestinian flags wave here and there: balconies, hotels, coffee bars. Palestine has reunited an often-divided Islamic world, a good reason to go against the eternal enemy (Israel) in a reunited Ottoman spirit, but scratching deeper, it often seems like a pretext. It might be a coincidence, but there isn’t a bookstore that doesn’t display a copy of Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf: certainly not a classic of Arab culture.

As always, I was saying, History takes strange turns. And meanwhile, we too, as we turn for a second to look at the sea, find a clamp on the car’s rear wheel: 50 euros black market to the policeman to remove it and tell us “Beautiful Italy!”… “Ah, Sicilians? Mafia!” Yet, my contacts at the embassy tell me that we must work on more and more cultural integration projects: it’s the usual story, my small cultural bubble thinks that a nice exhibition on the Mediterranean, some “flashed” videos on an iPad stuck in the wall of some gallery in La Goulette, can “move many more things than we think.” It’s the game, everyone plays their own irrelevant match alone.

6. Boats and Imbeciles

Data related to boats carrying Tunisian migrants bound for Europe through the cemetery of the central Mediterranean indicate an increase in landings towards Lampedusa, with departures from Tunisia, particularly from the Zarzis area, about 300 kilometers from the capital: there are fewer controls, and if possible, even more corruption. These boats, often crowded and in precarious conditions, carry migrants of various nationalities, but the number of Tunisians increases year by year, joining other Africans, mostly from Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Guinea, Mali, Senegal, and Sudan. Migrants, I’m told by CIS Tunis, with whom I collaborated on my Lampedusa projects, claim to pay sums ranging from 1000 to 2000 Tunisian dinars for the crossing. Luca Misculin, in his recent Mare Aperto (Einaudi 2025), accurately describes the millennia-long history of the Mediterranean for what it is: a great human epic of migrations, death, hopes, and constant movements. However, detailed narratives aside, the problem is how to cope with the general failure of the premise of post-Marxist philosophy: not to contemplate, but to change the world. Nothing changes; you decorate your reality and make a few moralistic rugs to feel better with friends at dinner: everything, and in this the Mediterranean remains an extraordinary metaphor, around us sinks and resurfaces in what is here called a “Mediterranean lasagna” made of layers. While reading that small masterpiece by Charles Olson, Call Me Ishmael. A Study of Melville (Minimum Fax, 2025), a friend sends me a video of an imbecile torpedoed from a debate at the Monk in Rome who compared me to Turetta, telling me “you should respond.” Charles Olson at one point writes, “it is necessary to understand every kind of fury and hatred”… and deep down, I thought, this imbecile is not so different from the reasons why we ignore what happens in Zarzis: we are incapable of complex thought, of diversifying the facts of the world, of abstraction other than that with which the majority thought feeds us… “we all have a family to support,” writes Olson, and this leads us to get by making idiotic videos of any silly person on social media, armed with moralism, while the world around them truly collapses. History, as I have repeated many times, turns quickly: it is already turning for all these imbeciles who will never read this far.

7.

From 2014 to today (July 2025), it’s estimated that over 30,300 people have died or gone missing in the Mediterranean: the average, which should perhaps be explained to some of those imbeciles so fixated on often irrelevant data, is about eight people per day… or approximately 3,030 each year. Most of these victims are recorded on the Central Mediterranean route. The most numerous shipwrecks occur off the coast of Tunisia, or at least along the route between Tunisia and Lampedusa: often my philosophy, dedicated to these themes, has seemed even more irrelevant than usual. Tunisian families often struggle to get news of their loved ones lost at sea, highlighting the human tragedy behind these numbers: over the years, I’ve met hundreds, and often, just talking about it is enough for them. All migrants, other Ettore Majoranas who show us that we are all on the wrong path, once again.