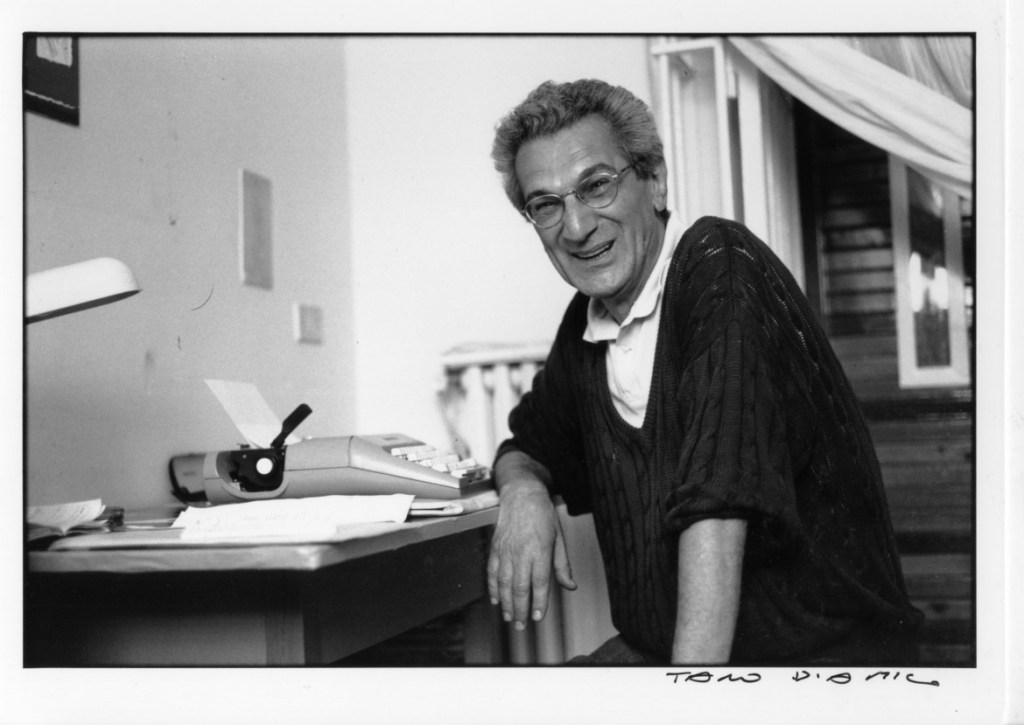

The film opens and closes with a phrase that, if we didn’t have Antonio Negri’s story to illuminate it, might seem like an expression of cynical disaffection. Instead, it is the keystone of his philosophy, his true recantation: “I prefer to know you than to recognize myself.” In this confession lies the seed of his entire philosophy of joy, of the power of conatus. Toni, the man—not the philosopher or the politician—always preferred discovery, movement, and the state of “being-in-the-making” rather than fossilizing into a photograph, into an identity. To recognize himself would mean accepting being a monument, an icon, a statue to be admired or to be torn down. But the real Toni, the one who shaves his beard every morning as an act of resistance in solitary confinement, cannot afford the luxury of stasis. Not even as a prisoner. Shaving isn’t a simple act of hygiene; it is a Spinozian gesture of conatus, of self-affirmation against the identity that has been stitched onto him. It is an act of removing, of taking away, to be able to start existing again every day, in every moment. It is about happy passions against sad ones.

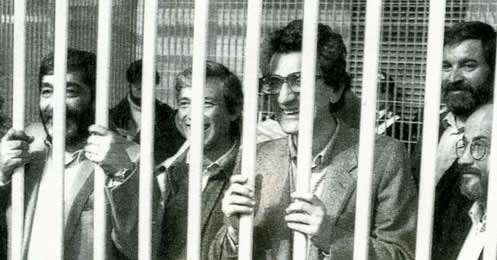

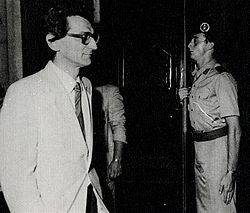

But what is he resisting? He resists the “world” that his daughter, Anna, attempts to represent. He resists the world that constructed the public image of Toni Negri, the man of “media filth” that was heaped upon him until the day he died (“the bad master is gone”). He feels at ease only when he is not asked to recognize himself in some glued-on label. His presumed voice on the archival tape from the Aldo Moro ransom phone call—a fragment that resurfaces like a ghost—is an echo of an era when words had weight and power, but today they are reduced to background noise, to a simple label. Of course, he hadn’t killed Moro, but meanwhile, L’Espresso delighted its readers with gadgets that showed Negri’s presumed guilt. Then, as now, media power supported the judiciary: filth was thrown on him. And here, Anna, with the brutal honesty that has always distinguished her as a director, shows us how this “filth” is not just an echo of the past, but a legacy that still today, for those with the courage to look, defines the present.

Conflict and the Power of Spinozian Substance

Anna Negri chose to tell a story of conflict, or rather, a series of conflicts: the family, the political, the philosophical. The film is not titled Anna, his daughter, but rather Toni, my father, because Anna is always in relation to him, like an expression of his substance. Despite herself, as she repeatedly points out in the film. “You’re his daughter? …oh.” Spinoza, whose work Toni studied extensively in prison, teaches us that everything that exists is an expression of the one substance, God or Nature. And Anna, his daughter, is an expression of Toni, who is in turn an expression of it. There is no hierarchy, but rather unity. Perhaps the film should have truly been called Anna, his daughter, I think as I write, to emphasize this ontological dependency, this tension that is resolved only in joy. It’s no coincidence that one of the most touching moments in the film is the joy that erupts, that breaks the narrative’s heaviness in the small, quiet moments when Toni suddenly smiles and Anna stops crying. That joy, that laughter, is the manifestation of conatus, of the power of existence affirming itself against every sad passion. In that moment, father and daughter are no longer two separate identities, but two expressions of the same substance who recognize each other, not in identity, but in the joy of their shared existence. As perhaps, I think to myself again, all daughters who were separated from their fathers by Italian “justice” feel.

The film, with its seemingly disjointed flow—made up of archival fragments, current footage, old home videos, and intimate conversations—helps us understand that conflict is not a problem to be solved, but the very engine of existence. And when family conflict is mistaken for violence, everything ends. In this sense, and otherwise it wouldn’t be a film about Negri, it becomes a perfect metaphor for political conflict. The “capitalist command” isn’t just an abstraction, but a power that seeps into relationships, deforming them, making them impossible. In my opinion, this film by Anna Negri has the great merit of showing this intertwining, of making us see how the personal is intrinsically political. Despite the desperation of a daughter who just wants to talk to her dad.

The Feminist Difference and the Other

One of the most interesting and, in my opinion, most courageous points of the film is the attention Anna dedicates to feminism through the distorted lens of Toni’s relationship with women, with his ex-wife Paola, with his companions from Lotta Continua… a minefield. Anna, with extreme sensitivity, brings forth the perspective of Paola, her mother, who perhaps experienced firsthand the selfishness of a man entirely absorbed by politics and philosophy. The film makes no excuses, it doesn’t try to justify, but instead questions Toni the man. And it does so by showing how Italian feminism, with figures like the beloved Muraro to whom Negri dedicated “the Italian difference,” fought a different battle than international feminism. A battle not just for rights, but for the recognition of a difference that is not a lack, but a power. From this point of view, Negri seems to have understood this aspect only halfway, or perhaps, due to his egocentrism, he failed to fully integrate it into his philosophy. Anna does it for him. She shows the “selfish man with Paola” and at the same time makes us understand that true joy, the true common good, cannot be achieved without recognizing the power of the other, their autonomous conatus.

The Past and the Future: 1976 and Today

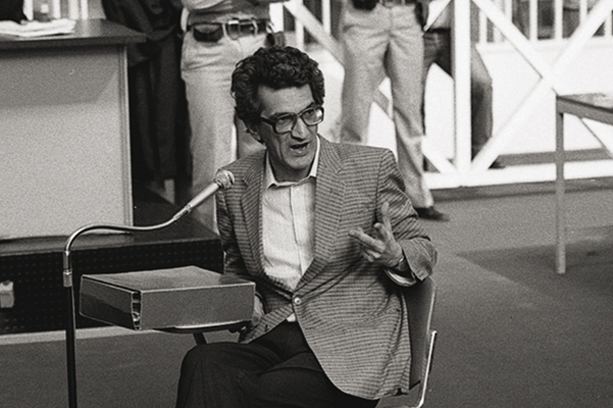

The film is imbued with a deep nostalgia for the 1970s, for that era when “everything seemed possible.” The 1976 youth proletariat festival at Parco Lambro in a now-vanished Milan, immortalized in a fragment of archival footage, is a visual representation of this utopia. A utopia of bodies moving together, dancing, building community. Naked, like the bare lifethat Giorgio Agamben and Toni Negri often discussed together. But Anna doesn’t limit herself to showing us this glorious past. She confronts us with its end, its implosion. And she does so in a brutal way, showing us the aforementioned L’Espresso insert from 1976, which called for a “psychiatric evaluation” of Negri. A document that is an act of accusation, an attempt to medicalize politics, to reduce complexity to a pathology… the Italian passion for supposed expert reports that are meant to prove the unprovable. The usual peak of reason. Today, in contrast, “everything seems impossible.” Perhaps we are experiencing the exponential inverse of the 1970s: violence and conflict today as well, but without any revolutionary ambition as their moral landscape. Thus, Anna Negri’s film invites us to reflect on this supposed transition. What happened? How did we get to this point? The film doesn’t give easy answers, just as Negri’s philosophy isn’t easy, but it suggests that the defeat was not only political, but also existential. A defeat of conatus, a victory of sad passions.

One question remains unresolved after watching the film: whether it is truly just an act of love and understanding from a daughter for her father, or if it is also, and perhaps above all, an attempt by Anna to be recognized, not by Toni, but by the world. In this sense, her choice not to call him “Dad” but always and only “Toni” is a political act. It is an attempt to transcend the filial relationship to establish a relationship between two people, between two autonomous conatus.

Toni, my father is a difficult film that demands an effort from the viewer, an attention that contemporary cinema is no longer used to asking for. But it is an effort that is repaid, especially for those, like the author of this text, who have studied the work of Toni Negri in depth. Because by the end of the viewing, we not only have a clearer picture of Antonio Negri, the man, the philosopher, and the politician, but we also have a hopefully deeper idea of what it means to exist in a world that seems to have lost the capacity for joy, that feeds on sad passions, and that has forgotten the power of a simple gesture like shaving one’s beard even while the world around them crumbles, in order to start existing again every day. The power of that beard is then the mantra, “I am alive, here, now.”

In this sense, philosophy was never an abstract exercise for Toni Negri—and here lies the great distance from Giorgio Agamben—but a practice of life. Or better, for the philosophers listening: a form of life. And Anna, with her film, has shown us how that practice was passed down, not through words, but through the body, the conflict, and the joy of a father and daughter whose feet are entangled in History.