A few years ago, I prepared a book of photos and texts from my travels and wrote a research project titled “Not Having a Notebook Handy” which I was about to exhibit in a well-known art gallery in Milan. Then I stopped, for no real reason. Here are some notes from this unfinished project.

“Many years ago I also tried to do something similar, something very vaguely similar: I ran away.” — Ettore Sottsass, Photos from the Window

Photos entered my books, my authorial works, and the columns I kept for newspapers and magazines quite late. However, the relationship between image and word has always been central to my development. And, not always having something with me to take notes, I equipped myself with every kind of camera during my travels, embracing the spirit of a beginner and the amateur soul.

I took thousands of photos, trying to capture something conceptual, but I always had to use words to bring out their essence. In substantial tribute to Ettore Sottsass, what follows is a combination of photos and words that have served to produce (perhaps) philosophy in other ways. And perhaps I believe I have produced more theory with these images, bridging the gap between an artist’s work and a traveler’s pastime, than with many pages of books.

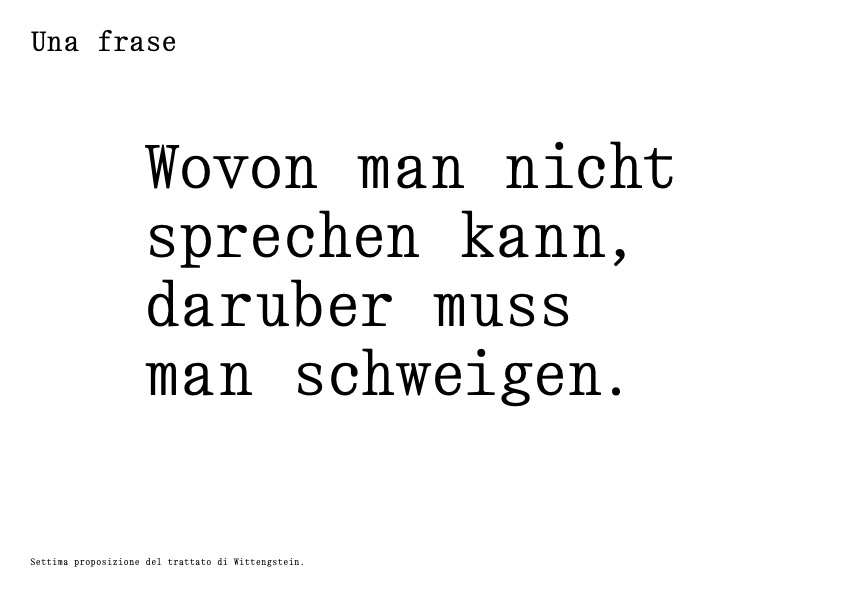

For years, we buried our sadness in desires for the future. ‘What will we do when we grow up?’ We ate our ration of nothing, a few coins, and the discount Coke they gave us in the cafeteria. It wasn’t yet fashionable to care about ecology; it was too early to face the reduction of minimal hope for the future. We studied, we ate, we hoped. And amidst this routine, the crater opened – the one between our desires and the world we would find outside of there. Has philosophy truly served any purpose then?

The humanity of the future, even for Nietzsche, was understood as a humanity without purpose, idle and new, spread across the world not so differently from any animal. But instead, we, the humans, have spread the animals in another way: envying them, we massacred them. I hope at least the meal was worth it.

A few years ago, I prepared a book of photos and texts from my travels and wrote a research project titled “Not Having a Notebook Handy,” which I was about to exhibit in a well-known art gallery in Milan. Then I stopped, for no real reason. Here are some notes from this unfinished project.

“Many years ago, I also tried something similar, something very vaguely similar: I ran away.” — Ettore Sottsass, Photos from the Window

Photos entered my books, my authorial works, and the columns I kept for newspapers and magazines quite late. However, the relationship between image and word has always been central to my development. And, not always having something with me to take notes, I equipped myself with every kind of camera during my travels, embracing the spirit of a beginner and the amateur soul.

I took thousands of photos, trying to capture something conceptual, but I always had to use words to bring out their essence. In substantial tribute to Ettore Sottsass, what follows is a combination of photos and words that have served to produce (perhaps) philosophy in other ways. And perhaps I believe I have produced more theory with these images, bridging the gap between an artist’s work and a traveler’s pastime, than with many pages of books.

“For years, we buried our sadness in desires for the future. ‘What will we do when we grow up?’ We ate our ration of nothing, a few coins, and the discount Coke they gave us in the cafeteria. It wasn’t yet fashionable to care about ecology; it was too early to face the reduction of minimal hope for the future. We studied, we ate, we hoped. And amidst this routine, the crater opened – the one between our desires and the world we would find outside of there. Has philosophy truly served any purpose then?”

“The humanity of the future, even for Nietzsche, was understood as a humanity without purpose, idle and new, spread across the world not so differently from any animal. But instead, we, the humans, have spread the animals in another way: envying them, we massacred them. I hope at least the meal was worth it.”

It’s no coincidence that many of these activities involve disguise. Is fruit still fruit? To disguise oneself, to change the aesthetic phenomenology of one’s person to transform it into someone or something else, is a condition intrinsically linked to living (the entire queer question, just to open apparently distant windows now and then, could be re-read as an immense game of stable identities becoming liquid). I would challenge anyone not to define our lives as substantially and mostly boring, domesticated by binary genders, ordinary jobs, obligatory relationships, punitive psychoanalysis, and social, economic, technological, and relational superstructures. But then, suddenly, new fruit arrives. It’s summer.

It seems that the greatest art curator of all time, Harald Szeemann, loved to conclude his conferences by quoting the famous motto of artist Bruce Nauman: “The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths.” The mystic is this dimension of “beyond reality” that a philosophy of play and salvation constantly aims for. We play because ordinary life bores us, often terrifies us; in general, something always pushes us to hope that it’s not “all there is” and that some possibility of escape is hidden everywhere.

Let’s imagine writing a world-book made of works and texts that constitute a new war against nature, an arcade with the premise that the war we’ve waged until now was wrong, and that the strategy must radically change by questioning some of the last anchors to the previous war.

We must truly question identities, not just with false statements imagining the definitive superposition of viewpoints or authorship. We can try to combat the latest hyper-naturalist tendencies, like non-vegetable diets that have massacred this planet. We must try to eliminate every legacy that suggests making art or philosophy means being anchored to reality, when instead it’s always a radical exercise in fantasy in which we constantly find ourselves navigating.

At least initially, the idea of a building narrow enough to ‘hug the palaces,’ which then widens into the sky once freed, expanding its section in reverse, was seen as a terrible challenge to the taste of the 1950s. Yet today, anyone knows they are facing a masterpiece if they observe such an exercise in brutalism. Fantasy and beauty, structural categories of human living, are first and foremost a break from the canon.

I believe that for a very long time now, there has been no notable break from the canon in philosophy; the reason is precisely a total lack of courage/fear of risk/adherence to tradition (choose the one that best fits the broader context of your work).